Generic vs. brand name birth control: But, I thought it was all covered?

Your insurance has to cover birth control under the Affordable Care Act—so why are some women still paying out of pocket?

UPDATE: President Biden has opened the enrollment period for the Affordable Care Act health insurance plans for 2022. You can now enroll in one of these plans until January 15, 2022, at healthcare.gov. Some states have their own open enrollment periods and websites for signing up. Check to see if your state does. We also have more information about how to get insurance and learn what kinds of plans to watch out for.

—

I strolled into my local pharmacy on January 11, 2013, with my wallet tucked into the depths of my backpack, confidently out of reach: I was picking up my first pack of free birth control (that is, birth control that’s covered by my insurance without a copay).

With a smile I turned on my heel from the pharmacy counter—birth control in hand and wallet still untouched—and anxiously shuffled outside to find an isolated square foot of NYC sidewalk and tweet my glory to the world.

I repeated this victorious experience in February, March, April, and May. It wasn’t until June that I left the pharmacy with no smile or glory: For some reason, my “free” birth control now cost me $85.

The pharmacist gave a few possible explanations—none of them sounded completely convincing, but I wasn’t educated enough to be sure. All I knew was that as soon as people started to throw around words like “deductible,” my mind wandered to cooler things. Most things related to health insurance never made sense to me, so I assumed it was some sort of a fluke and hoped maybe the price would go down the next month.

It didn’t. In July, I spent another $85 on something that just two short months ago had been covered by my insurance. So, I took action and got educated about the intricacies of insurance coverage of birth control.

The Affordable Care Act

My first step was to revisit the basics of the Affordable Care Act (ACA for short, a.k.a. ObamaCare). Getting my facts straight prior to calling my insurance company meant I could make a sound argument if needed.

In a nutshell, a provision of the ACA requires insurance companies to cover all contraceptive methods that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) without any out-of-pocket costs. Some religious organizations, like churches and other houses of worship, are exempt from the rule; some plans were “grandfathered” in, meaning they’re exempt for now but will eventually have to comply.

Reviewing the ACA basics didn’t really provide much insight into why my birth control suddenly cost $85. Clearly my plan hadn’t been grandfathered since I had those four blissful months of coverage, and the user experience (UX) design firm I worked for definitely wasn’t an exempt religious organization. So I delved further, scanning legal jargon I found on government websites.

The details:

Insurers are required to cover all methods of contraception, but they aren’t required to cover all brands of contraception, especially if a brand name birth control comes in a cheaper, generic form.

When insurers decide which brands to cover and how much coverage to offer, they must comply with the guidance of the U.S. Health and Human Services Department (HHS) in addition to considering how much it will cost them.

While these juicy, jargon-y details helped put my problem in context, they still left me curious as to how I had once frolicked in a meadow of fully covered birth control and had now somehow found myself wading in a costly birth control swampland. To my knowledge, my birth control didn’t have a generic equivalent.

It was time to do my least favorite thing in the world: Call my insurance company for more information.

The nitty-gritty: Tiers and formularies

Once I got someone on the line to help me, I explained my situation. The customer service dude factually and nonchalantly stated that the kind of birth control I was on was “tier three” and that’s why I was being charged—not because of any mistake as I had assumed.

I argued that regardless of its “tier three”-ness, I had once gotten my birth control without having to pay a copay at the pharmacy. Then I mentioned the ACA provision.

He sounded surprised when he said, “Oh. Really?”

It was time to go.

I visited my insurer’s website and read about my benefits. I also read the documentation about my health insurance policy (which, fun fact, sounds like a language made up by super-mundane robots).

I learned that many health insurance plans have something called a “formulary,” which is also known as a preferred drug list or a prescription drug list (PDL). This list consists of all the prescription drugs the insurance plan covers and the amount it will cost members to use those drugs. These lists arise from negotiations about drug cost and supply between an insurer and a drug company. Each plan’s formulary is different and drugs that aren’t on your plan’s formulary can be pretty pricey.

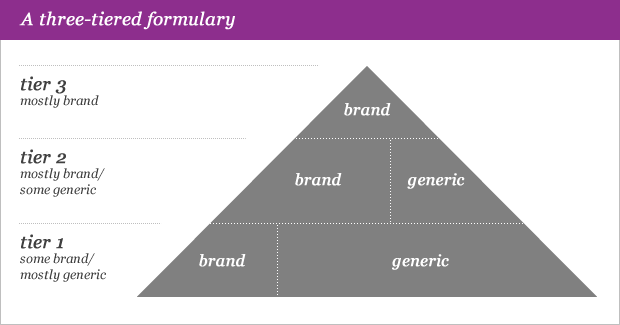

As it turns out, many health insurance plans have a drug pricing system that organizes its formulary into “tiers.” The drugs that fall under the first tier are typically the most affordable, and the prices go up from there. Often the majority of the first-tier drugs are generic with a few brand name drugs—these brand name drugs are usually in the first tier because they don’t have a generic equivalent.

While this, too, all made perfect sense to me, it still didn’t explain why my tier three birth control would’ve ever been covered. That’s when I called the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) Pill4Us hotline.

Putting it all together with NWLC

NWLC clarified for me that the ACA requires all unique methods of birth control to be fully covered. That means that if a brand name contraceptive method doesn’t have a generic equivalent, it has to be covered.

NWLC informed me that formularies change frequently—and that doesn’t just affect birth control. Any and all drugs in a formulary can change tiers or be removed as often as an insurance plan chooses. The problem is that notification about this sort of thing happens at the pharmacy checkout counter (when it’s too late to explore other options) or not at all.

What happened in my situation was that my birth control was bumped from a lower tier to a higher tier when its generic was added to the formulary.

NWLC told me that generics have the same active ingredients as brand names according to the FDA. In fact, if your health care provider prescribes you a brand name drug and doesn’t write “dispense as written” on your prescription, the pharmacist can give you the generic version. And thanks to the ACA, if my doctor and I determined that the generic version affects me in any kind of adverse way, I’d be able to contact my insurance provider about waiving the out-of-pocket costs of the brand name.

I made an appointment with my doctor and brought my health plan’s drug formulary list with me to my visit. My doctor was able to see what generic equivalents were in my formulary so I could make a clean switch, which I did with no issues and, best of all, with no out-of-pocket cost.

If you find yourself confused about the price of your birth control, NWLC gives the following advice:

Find out if this part of the ACA applies to your plan at this point or if your plan is “grandfathered” and doesn’t have to comply yet. This NWLC phone script can help with the call to your insurance provider.

Get the NWLC toolkit, “Getting the Coverage You Deserve.” It will help you confirm whether you’ve been wrongfully charged for your birth control and how to appeal that charge. You can use the toolkit’s sample letters to make an appeal about your charge.

Finally, if you need help with anything, call NWLC’s free hotline (1-866-745-5487) or email NWLC at CoverHer@nwlc.org. They’re there for that reason, and your phone call helps them to know what kind of problems they can tackle. It’s a win-win.

How do you feel about this article?

Heat up your weekends with our best sex tips and so much more.